Fiber in C++: Understanding the Basics

Fiber, a less known concept compared with coroutine, is a pretty powerful addition to cooperative multitasking. As a graphics programmer in game industry, I totally appreciate the great flexibility that fiber brings on the table. As a matter of fact, I feel the tech is a little bit underappreciated due to the lack of sufficient public materials talking about fibers.

In this blog post, I will put down some of my learnings about fiber basics. Everything mentioned in this post will be specifically about C++ even though similar concept exist in other languages as well. Readers who have zero knowledge about fibers will be learning what it is and how we can take advantages of it in graphics rendering.

Multitasking

As we all know that modern games commonly require quite some processing power so that they react to gamers in a timely manner. The performance improvement made in single core CPU could no longer keep up with the sheer computational demand quite a while ago. To no one’s surprise, the industry has shifted from single thread game engine to multithread engine more than a decade ago. Multithreading has became an essential part of game development. It is also a very mature tech that is well supported and optimized by major operation systems.

With multithreading, it is necessary to split the computation of a frame into multiple sub tasks depending on their characteristics so that each thread gets something to do. Some tasks process physics, some process rendering, the list goes on. It is inevitable to introduce some dependencies between the tasks. Respecting the dependencies requires careful synchronization. In order to correctly manage the tasks, job systems (sometimes named as task systems) are introduced in game engines. They are used to harness the multi-core power provided by CPUs.

Limitation of Preemptive Multitasking

It is not uncommon to see more active threads ‘running’ than the number of physical cores. In order to give users an illusion of multitasking, operating systems commonly execute multiple tasks in an interleaved manner. Each thread gets a fraction of the whole timeline of the physical cores. As long as the frequency of swaping thread is high enough, users will feel like they are running at the same time. This model is what is commonly known as preemtive multitasking[1] .

Even though this model works fairly well for majority of applications, game development is one of the rare domains where developers will try to squish every tiny bit out of the target platform. There are some loss of flexibility in preemptive multitasking that can be annoying sometimes. Specifically, the following facts about preemptive multitasking are what bother game developers.

- Context switch happens at a frequency that is not directly controlled by developers. This is exactly how the OS supports multitasking in the first place. However, this is not cheap as it requires a trip in the kernel. And whenever it is not needed, it can be considered as a waste of resource.

In order to understand better where this waste comes from, imagine if we have 10 tasks running in the first 2 ms of a frame on a machine with only 4 physical cores, do we really need to create the illusion that the 10 tasks are all running at the same time? The truth is that we don’t, all we care is that within the time limit of a frame that all the tasks within this frame are all finished in a correct order. However, this is not something the OS knows, having to preserve this behavior is the root cause of the waste. - Thread scheduler is highly operating system dependent. Whenever an active thread is about to be put on hold, it is the OS who decides which next thread gets the chance to take over the physical core for the next time window. Even though most OS interfaces offer some level of control, like thread priority, the scheduling algorithm is transparent to programmers. And this can be problematic from time to time.

Again, the scheduler has no prior knowledge about the game engine. It will have to treat the system as no different than a generic system. So the next thread to be ran may not match developers’ expectation sometimes.

To some degree, we can think of the preemptive multithreading as virtual threads fighting for physical resources. No thread is in full control in this game since the scheduler can preemptively pause a thread any time. And this clearly comes at some cost and uncertainty.

If these are within tolerance, what further pushed some game studios to move towards a more efficient system design is a problematic case that a task needs to wait for some inputs that is not yet produced by other task.

-

An impractical solution would be to schedule more threads than the number of physical cores and yield the thread’s control if it waits for something so that OS can schedule other thread on it. This may sound fine. Unfortunately, it has flaws.

-

First of all, the OS has no idea when the inputs are ready, it will keep trying to put this thread back on the physical core to make attempts to resume it from time to time. This is clearly very inefficient since until the input is ready, all prior attempts are useless effort that only waste hardware resources.

-

If this doesn’t sound scary enough, an even worse situation is that the system could end up in a dead lock state if all threads in the thread pool are waiting for something that are not ready, which will eventually hang the game since pending tasks can’t find a thread to run it on and all threads are yielding due to the lack of inputs. To solve the problem

- One option is to create new thread in such a case to make sure pending tasks can always find a thread to run on. Put aside the fact that creating a thread is not cost free, this would not only increase the complexity of the system, but also introduce more threads as well, meaning potentially more preemption happening in the future.

- A different approach is the job nesting system, which, rather than putting the current job on hold when waiting for something to be ready, grabs another job and execute the new job on top of the existing call stack. A big problem of this solution is that the tasks’ call stack will possibly stack on top of each other and there is no way that the job on bottom of the stack to finish before what is on the top to finish first.

There are other ways to tackle the problem. However, the ideal solution is to yield when a task needs to without paying significant cost. Unfortunately, with preemptive multitasking, this can’t be easily achieved.

-

-

An alternative solution would be to split the task into two at the boundary of the wait. Even though this sounds like a more practical solution, this kind of solution is more like a last resort that is very unlikely scalable as certain cases show up more frequently, which will force us to create more tasks.

If there is anything to blame, it is that preemptive multitasking doesn’t allow tasks to yield themselves during execution.

Cooperative Multitasking

Cooperative multitasking is different in a way that it allows programmer to take over the scheduling, rather than handling over to the OS. As its name implies, it allows different tasks to cooperatively work with each other. This would mean that they only give control when they yield and other tasks will choose to trust this running task that it will give control to them at a reasonable point. With this trust established, there is no need to preemptively interupt a running task without its permission like the OS does with preemptive multitasking. Rather than tasks fighting for hardware resources, the cooperative multitasking is more like tasks are happily working together like a family.

With this design, each task will carry more responsibility as if they don’t give control to others, others will not have any control at all. The need to yield control to other tasks requires the subroutine to yield when they want to. Such a subroutine is commonly viewed as a more generalized version of regular subroutine, it is called corountine. It is the most commonly known solution that allows us to program a thread so that it works cooperatively.

Of course, even a program is fully done through cooperative multitasking, it doesn’t mean that no preemption will happen since the OS will need to schedule other back ground applications, such as email, to run on the shared physical cores from time to time. But minimizing the context switch within our own application already offers a lot of value on the table.

Before we move forward, for those who are not familiar with the term of subroutine and coroutine. A quick explanation is as below

- Subroutine is a thing that can be invoked by the caller and it can return back the control back to the caller, which called it. I believe all programmers would quickly realize that the concept of function is a realization of subroutine.

- Coroutine has all the properties a subroutine has. Besides, it can suspend itself and return the control to the caller. And it can also resume at a later point and pick everything up at the suspended point even on another totally different thread.

In order to keep the post short, it is assumed that readers would have some basic coroutine knowledge. For readers who are not very familiar with coroutine in C++, here is an awesome talk in Cpp con.

Basics about Fibers

Apart from Coroutine, Fiber is an interesting addition as a solution to cooperative multi-tasking. Fiber is quite a lightweight thread of execution. Like coroutine, fiber allows yielding at any point inside it. To some degree, we can regard fiber as a form of stackful coroutine, which is not available in C++ programming language. By not available, I mean there is no native language support for that. There are certainly libraries like boost that support this kind of coroutine or even fiber.

Don’t be intimidated by its fancy name, fiber really is just a method that allows programmers to jump between different stack memory without regular return command. Since it offers the ability for us to jump between different call stacks, we can allocate our own stack memory and use it as our fiber stack.

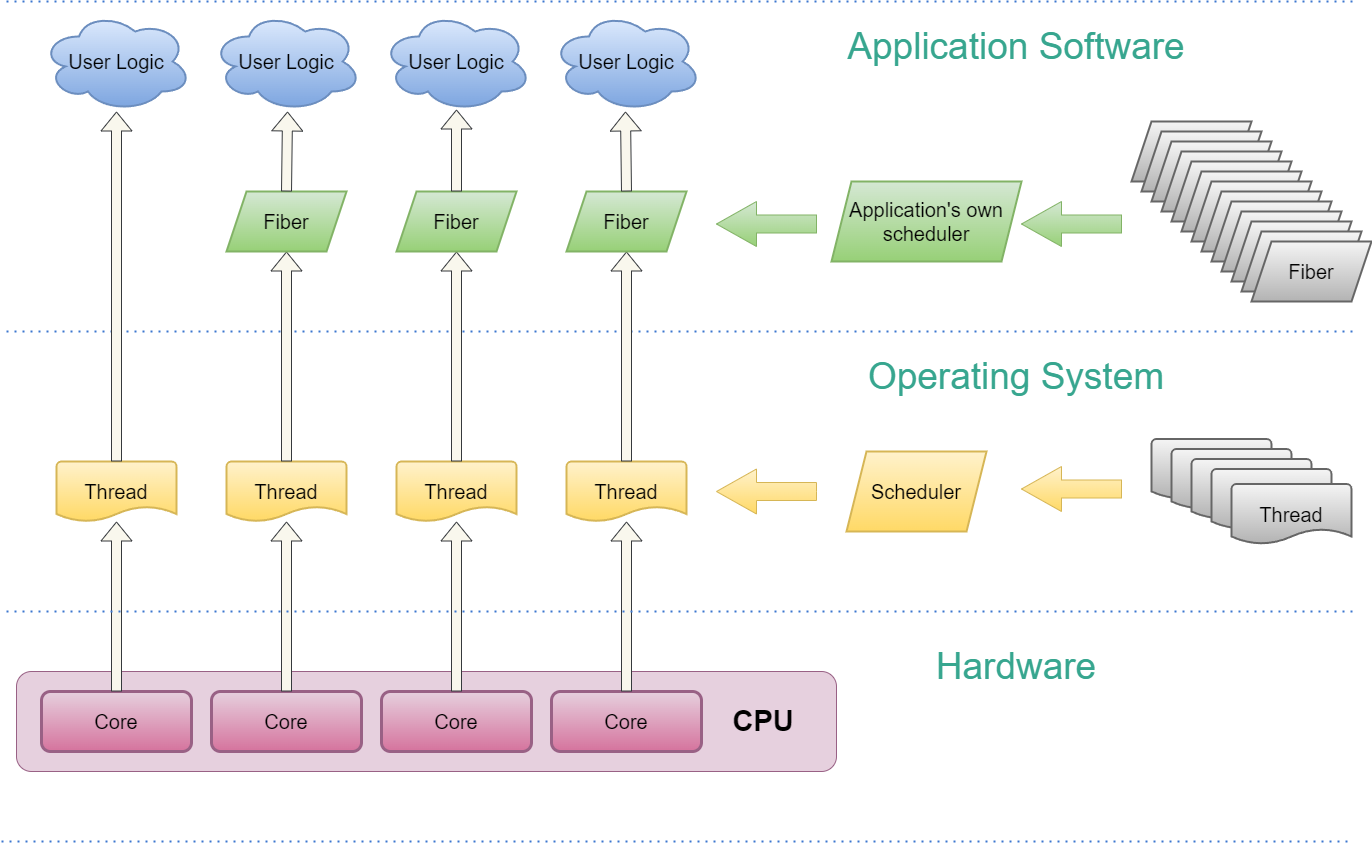

Below is a diagram that demonstrates how fibers fit in a program.

We can see a few things from this diagram

- User logic code can be ran on either a regular thread or a fiber, which itself runs on a thread.

- Unlike thread, fiber’s scheduler is application specific, meaning software developer needs to carry over the responsibility to schedule fibers. OS will no longer help with this.

- As hinted in the diagram, user can commonly create a lot more fibers than threads as things like stack memory allocation are a lot more controllable by developers.

- Though not shown in the diagram, a system with fiber commonly use thread affinity to fix threads on dedicated cores for better performance and the number of back ground threads doesn’t need to be high. Commonly only a few low priority threads are needed for blocking operations like IO.

There is a lot more to explore. We will mention them in following chapters with more details.

Difference between Fiber and Thread

Compared with fiber, thread is a lot well known concept. With the assumption that all readers already have a solid understanding of threads, below are some very obvious difference between a thread and a fiber.

- A thread can be scheduled by the operating system and runs on a physical core of the CPU. While a fiber can only be ran on a thread. We can think of fiber as a more high level concept as it sits on top of a thread.

- Even though, both of them could support multi-tasking. Threads support multi-tasking through the OS’s preemptive style scheduling. Fiber supports multi-tasking by asking the programmer to take the responsibility to schedule them in a well-behaved manner.

- Thread switching is a lot more complicated than a fiber switch. Thread switch requires the program to take a trip in the kernel mode and can be a lot more expensive. A fiber switch is nothing but swapping the registers with previously stored fiber context.

- The memory for call stacks for a thread is controlled by the OS, while the memory for a fiber stack can be explicitly controlled by programmers. This offers great flexibility as programmer commonly have knowledge of the system they are building so that they can simplify things with those assupmtions.

- Thread local storage is safe for threads, but they may not be 100% safe with fibers as some system chooses to schedule fibers on different thread between executions of a same fiber.

- Native operating system offerred synchronization primitives, like mutex, will not work on fibers if fibers can resume on other threads than the one they were suspended on. We have to extremely careful when using sychronization primitives within a fiber.

Difference between Fiber and C++ Coroutine

It is a lot easiser to compare thread and fiber than comparing fiber and coroutine. Please be mindful that the coroutine concept that we are talking about here is merely the C++ langauge supported coroutine. We are not comparing fiber with any custom implementation of coroutine.

- C++ coroutine is a language concept. As a matter of fact, C++ only started to support language wise coroutine from C++ 20. While fiber is an OS level concept, commonly provided by OS library interface. Fiber can totally be implemented by progarmmers themselves with assembly languages. Later we will see how this can be achieved.

- Coroutine functions are generally a bit more complicated to implement. There are a few concept for configurations, like coroutine handle, promise. Programmer will have to either implement their own type or use the types offered by a third party library to implement a coroutine function. While there is really no such a concept as a fiber function, a regular function can take advantage to yield within it without any special treatment.

- C++ coroutine will siliently added more configuration code to implement coroutine. Such hidden code is not only compiler dependent and can vary on different platforms as well. Programmers will have little control on how these code are generated. On the other hand, since fiber is not a language level concept, the compiler will do nothing special about it. There is good and bad about the difference here

- One advantages of coroutine is that all variables will get proper destruction when coroutine is ended. It can be ended either by quiting the coroutine function at the co_return command. The other way to end a coroutine’s lifetime is to end the life time of the coroutine handle even if the coroutine is not finished executing yet. Of course, only variables that are actually touched within the execution progress will get destructed. Variables not even touched in coroutines will not be destructed as they never get constructed in the first place.

Unfortunately, fiber can’t do so. There is no easy way to track all the local variables in fibers and properly destruct all of them if the fiber gets suspended and got killed. It is programmer’s responsibility to make sure that all the local variables that needs destruction to be destructed at a proper time before killing a fiber.

An interesting example is smart pointers. Smart pointers in C++ is done by bundling all heap allocating to a stack allocation. As when the program ends, all stacks are gone, it can be sure that all the heap memory allocation that is bound to smart pointers will be freed as well. However, such a mechanism will fail to protect your heap allocatin memory leak in the context of fiber. We will mention that once we talk about the implementations of fiber later to avoid confusing readers here. - Since C++ coroutine is a language level concept, compilers are in good position to optimize as much as possible. One example is that compiler can choose to inline coroutine function sometimes, even making them disappaar in the thin air[3] . Such an optimization is clearly not possible with fiber. Later we will see, we will have to do something to prevent the compiler to optimize the code so that fiber logic can behave as expected.

- One advantages of coroutine is that all variables will get proper destruction when coroutine is ended. It can be ended either by quiting the coroutine function at the co_return command. The other way to end a coroutine’s lifetime is to end the life time of the coroutine handle even if the coroutine is not finished executing yet. Of course, only variables that are actually touched within the execution progress will get destructed. Variables not even touched in coroutines will not be destructed as they never get constructed in the first place.

- Coroutine’s memory management is a bit more transparent than fiber. The size of the memory allocation is highly dependent on the compiler. For fiber, programmers are required to allocate a piece of memory as stack. It is up to programmers to decide how many bytes they need for the fiber execution. Of course, programmers need to make sure what is ran on the fiber will not cause stack overflow by allocating enough memory for the fiber stack.

- Coroutine can return a value, while fiber doesn’t allow programmer to do so in a traditional return value way.

- We can finish a coroutine function by running the code through the end. While we can’t proceed to the end of a fiber entry function as there is no proper return address for fiber entry function.

- C++ coroutine is asymmetric coroutine, which allows the coroutine to return the control to the caller, only the caller. There is no way for a coroutine function to yield its control to other coroutine that was suspended before. While there is a concept named symmetric coroutine that allows one coroutine to yield its control to another coroutine. Fiber is symmetric by default. It actually never returns to the caller code, it only yields to another fiber.

- C++ coroutine is stackless, meaning that it is only allowed to yield within the coroutine function itself. If your coroutine function calls another regular function, it is disallowed to yield the control back to the caller that calls the coroutine function. Fiber does allow yielding the control at any depth in the call stack.

Above are some of the major differences between a fiber and C++ language level coroutine. Among all these differences, the last two are almost deal breakers for flexible job system implementation. Of course, there are certainly examples of using coroutine to implement a job system [4] [5] , it is techinically possible. But the flexibility offered by fiber is a lot more powerful than what coroutine offers on the table. Naughty Dog’s game engine’s job system is a successful example of using fibers to parallelize game engine [6] .

Fiber Implementation

Understanding the details in fiber implementation can be rewarding. Even though fiber offers great flexibility on the table, the implementation of fiber is nothing but a few hundred lines of code.

In this section, we will go through a detailed fiber implementation on x64 architecture, a similar version working on arm64 architecture is also provided in the form of source code.

Unlike a high level feature implementation, fiber’s implementation is a bit unnormal and hacky. It requires programmers to have solid understanding of how CPU handles the call stacks during program execution. So before we move forward with a detailed fiber implementation, we will need to take a look at some basics of how CPUs handles call stack on x64 and arm64 respectively.

The implementation detail of fiber in assembly languages on Arm64 architecture is quite similar to what needs to be done on x64. The biggest difference is the registers set is different from each other. So we will not repeat a similar process. Readers who are interested in its implementation can take a look at my implementation with the above link.

Fiber implementation highly depends on ABI (Application Binary Interface). In this blog post, the fiber implementation on x64 is built upon System V ABI. Different ABI requires a different fiber implementation.

Target Platform Architecture

Rather than going through everything, which is clearly not possible, I will only briefly mention what is related to fibers. And we will only spend our time on a 64 bit program. Though, it should work in a similar way in 32 bit programs.

In the following two sections, we will be uncover the mystery of how CPU handles call stacks under the hood. Here is the high level program that we will look at. I intensionally keep the program extremely simple and meaningless so that we can focus on the call stack rather than being distracted by something else.

1int Interface(int g) {

2 int k = g * g;

3 return k * k;

4}

5

6int main(int argc, char** argv) {

7 int a = Interface(argc);

8 return a;

9}x64 Architecture

There are in total 16 64-bit general purpose registers in modern x64 CPU architecture. They are RAX, RBX, RCX, RDX, RSI, RDI, RBP, RSP, R8 to R16 respectively. Apart from the general purpose registers, there is also a special register named RIP, the instruction pointer, which tells the CPU what to execute next.

Besides these registers, there are certainly more. For example, all x86-64 compatible processors support SSE2 and include 16 128-bit SIMD registers, XMM0 to XMM15. It is fairly common to see AVX SIMD as well, this is achieved through another 16 256-bit registers, namely YMM0 to YMM15. Further more, there is AVX-512, which is an extension that allows the CPU to process 16 32-bit number operations at a same time. CPUs that support this have another 16 registers (ZMM0-ZMM15), each of which is 256-bit long.

It is very common that we store something in a register and fetch the value from this register later. However, it is not uncommon that we need to change the value of the register in-between the two instructions, especially if there are function calls inbetween. In order to make sure by the time the register is read, the value is not overwritten, the value has to be stored somewhere (commonly on the stack) before it is changed in between. There are a few registers that are callee-saved, which means that the callee needs to save the register before touching the registers and restore the value of the registers before leaving the function so that the caller does not even know the value of the register is changed. These registers are RBX, RBP, R12 to R15. All other regiters are caller saved, which means the opposite, the callee can change the values of the registers anytime they want by assuming that the caller will make sure the values of the registers will surive the callee’s instructions.

Next, let’s take a look at the aseembly code produced by g++ compiler below. Please be noted that in order to understand how CPU works with its registers to support stack properly, I will have to disable compiler optimization as otherwise the compiler may choose to optimize them out by avoiding using the rbp register so that it can be used as another general purpose register. Sometimes it even inline the whole function without a jump at all. Here is the assembly code generated by g++ 7.5.0 on Ubuntu,

10x400667 <Interface(int)> push %rbp

20x400668 <Interface(int)+1> mov %rsp,%rbp

30x40066b <Interface(int)+4> mov %edi,-0x14(%rbp)

40x40066e <Interface(int)+7> mov -0x14(%rbp),%eax

50x400671 <Interface(int)+10> imul -0x14(%rbp),%eax

60x400675 <Interface(int)+14> mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

70x400678 <Interface(int)+17> mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

80x40067b <Interface(int)+20> imul -0x4(%rbp),%eax

90x40067f <Interface(int)+24> pop %rbp

100x400680 <Interface(int)+25> retq

110x400681 <main(int, char**)> push %rbp

120x400682 <main(int, char**)+1> mov %rsp,%rbp

130x400685 <main(int, char**)+4> sub $0x20,%rsp

140x400689 <main(int, char**)+8> mov %edi,-0x14(%rbp)

150x40068c <main(int, char**)+11> mov %rsi,-0x20(%rbp)

160x400690 <main(int, char**)+15> mov -0x14(%rbp),%eax

170x400693 <main(int, char**)+18> mov %eax,%edi

180x400695 <main(int, char**)+20> callq 0x400667 <Interface(int)>

190x40069a <main(int, char**)+25> mov %eax,-0x4(%rbp)

200x40069d <main(int, char**)+28> mov -0x4(%rbp),%eax

210x4006a0 <main(int, char**)+31> leaveq

220x4006a1 <main(int, char**)+32> retqWhat is shown above is the assembly language code for the two functions in the above C++ program. Please be mindful that the same program may produce very different assembly instructions with different compilers, but the general structure of the program should be similar to each other. Rather than going through every single instructions, we will only focus on those that are relevant to our topic. Below is what happens when this program is executed in order with some instructions skipped as they are not relevant.

- At the very beginning, the

RIP’s value is 0x400681, which means that the next instruction is thepush %rbpthat is located at the begining of main function. - Starting from 0x400681, the first thing CPU does is to store the

RBPregister on the stack memory. This push operation will also decrease the value ofRSPby 8.RSPis the stack pointer that points to the current top address of the stack. Please be noted that on x86/x64 architecture, the address of the stack goes downward whenever it grows. In this case, sinceRBPis a 64-bit registers, the stack pointer (RSP) needs to decrease by 8 to avoid the storedRBPbeing overwritten by anything else. Of course, after this instruction is executed, theRIPwill be bumped as well so that CPU knows what to execute next. - The next thing it does is to set the current stack pointer’s value to the register of

RBP. This will give us some insight of whatRBPis. It is not difficult to see that theRBPregister keeps the value of the bottom of the current function’s stack frame. - By skiping some instructions that are not relevant, let’s take a look at the instruction 0x400695. This is the instruction that invokes the

Interfacefunction. What the CPU does here is that it will first push the next instruction’s address, which is 0x40069a, on the stack. Of course, since it is a push, theRSPwill be decreased again to keep the pushed value safe. This is what is commonly known as return address. Specifically, it is the next instruction for the CPU to execute after finishing the callee function, which isInterfacein our case.

Of course, besides pushing the next instruction’s address on the stack, the CPU needs to execute the first instruction in theInterfacefunction. This is achieve by changing theRIPregister to 0x400667 so that the CPU knows what to execute next. - Looking at the first instruction in the function, which is at the address of 0x400667, this immediately reminds us what is done at the beginning of the main function, pushing the

RBP’s value on the stack. At this point, we know what theRBP’s value is, it is the base address of the main’s call stack frame. Because we are currently in theInterfacefunction, we will need to make sure theRBP’s value is the bottom of theInterfacefunction’s stack frame, rather thanmainfucntion’s stack frame. To do so, we simply need to move the value ofRSPtoRBP. However, themainfunction’s stack frame’s bottom information will be lost. We mentioned above thatRBPis a callee saved register, this means that the callee (Interface) is responsible to make sure it appears that theRBPis not changed from the caller’s perspective. To do so, we simply need to push theRBPon the stack before assigning a new value toRBP. And this is exactly what this line is all about. - The next instruction 0x400668 is quite similar to the 0x400682 instruction we visited before. Its sole purpose is to make sure

RBPkeeps the value of the bottom of the current function’s stack frame. - Instructions between 0x40066b and 0x40067b (inclusive) are simply the implementation of the body of the function. It is actually quite self-explanatory even to someone who is not familiar with assembly languages. One thing to be mindful here is that the

RSPis not changed throughout the instructions. - Looking at 0x40067f next, what the CPU does is to increase the

RSPby 8 and take the current value pointed by theRSP. This is what we commonly known as poping the stack. Since theRSPstill points to the next address adjacent to the address that has the oldRBP’s value, the bottom of the main’s call stack frame, this instruction will erase what is currently stored inRBPand restore theRBPvalue before leaving the function. - Right before quiting the function, CPU will execute

retqinstruction. What this does is to increase the value ofRSPby 8, take the value pointed byRSPand assign it toRIP. Careful readers may have already realized that this is exactly 0x40069a since we stored this value in the instruction of 0x400695.

At this point, we have fully visited how a function is called. As we can see, RBP and RSP play a critical role here in preserving the call stack information and make it visible to the CPU. Again, in reality, a lot of the times compilers will try to optimize it so it is quite possible that we won’t see some of these in release build. Please be noted that this optimization of RBP is by no means the same thing as compiler trying to optimize the function by inlining it. It still jumps the RIP to another different code fragment that belongs to the Interface function.

10x4004d0 <Interface(int)> mov %edi,%eax

20x4004d2 <Interface(int)+2> imul %edi,%eax

30x4004d5 <Interface(int)+5> imul %eax,%eax

40x4004d8 <Interface(int)+8> retq

5

60x4003e0 <main(int, char**)> jmpq 0x4004d0 <Interface(int)>Above is the assembly code produced with (level 3) optimization by the same compiler. In order to prevent the compiler from inlining this function, I moved the Interface function to a separate compilation unit.

As we can see from it, it does incur a jump instruction in the main function rather than expanding what is inside Interface in main.

There is an option -flto for the compiler to perform link time optimization, which allows the compiler to optimize across different compilation units. Similar option is available in all major C++ compilers. With this option, the following assembly code will be produced.

10x4003e0 <main(int, char**)> mov %edi,%eax

20x4003e2 <main(int, char**)+2> imul %edi,%eax

30x4003e5 <main(int, char**)+5> imul %eax,%eax

40x4003e8 <main(int, char**)+8> retqAs we can see from the above code, the jump instruction is fully removed, meaning the function is already inlined with this optimization. Later we will see that we will need to prevent this from happening in the context of fiber switch.

Arm64 Architecture

Besides x64 architecture, I would also like to briefly mention about the Arm64 architecture in this post due to the growing popularity of the platform, especially after Apple’s new Mac lineup with Apple Silicon. The purpose of the introduction of fiber in this post is mainly targeting on game development. It would be a blocker for commercial adoption of the tech if there is no solution on Arm64 since most mobile devices, along with Apple Silicon Macs, run on this platform.

Below is a quick summary of registers available on Arm64 CPUs.

- X0-X29: These 30 registers are mostly for general purpose usage. Programmers can use most of them for anything they want. Though common practice will assume some specific usage of a few registers, like

X29is commonly used as frame pointer, something similar toRBPon x64 arthitecture. - X30, LR: Different from x64, there is a dedicated register for keeping track the return address when a function is invoked. And this register is

X30, sometimes also referred asLR. - SP, XZR: This is the stack pointer on Arm64 architecture, the analog of

RSPon x64. However, a minor difference here is that this register can also be used as zero register when used in non-stack related instructions. - PC: This is the Arm version

RIP, the instruction pointer or program counter. It records what is to be executed next by the CPU. - V0-V31: These are 32 registers that is used for float point operations and Neon, 4-way SIMD, operations.

Above are just part of the whole register set. There are more registers like D0-D31, S0-S30 and etc. However, we are only interested in learning the above registers as only these matter when we implement fibers on Arm64 CPUs.

Similar to x64, some of the above registers are callee saved. They are X16-X30, V8-V15. The rest of available registers are all caller-saved.

Again, let’s start with the assembly code produced without optimization. In this case, I compiled the source code with Apple clang of version 14.0.0 on MacOS Ventura 13.1.

First, here is the code for the main function

10x100003f7c <+0>: sub sp, sp, #0x30

20x100003f80 <+4>: stp x29, x30, [sp, #0x20]

30x100003f84 <+8>: add x29, sp, #0x20

40x100003f88 <+12>: stur wzr, [x29, #-0x4]

50x100003f8c <+16>: stur w0, [x29, #-0x8]

60x100003f90 <+20>: str x1, [sp, #0x10]

70x100003f94 <+24>: ldur w0, [x29, #-0x8]

80x100003f98 <+28>: bl 0x100003f50 ; Interface at main.cpp:5

90x100003f9c <+32>: str w0, [sp, #0xc]

100x100003fa0 <+36>: ldr w0, [sp, #0xc]

110x100003fa4 <+40>: ldp x29, x30, [sp, #0x20]

120x100003fa8 <+44>: add sp, sp, #0x30

130x100003fac <+48>: ret

Since we already have some experience reading assebmly code, let’s go through this one a bit quicker.

- Starting from the beginning, the

PC(Programmer counter) register is 0x100003f7c, meaning the first instruction issub sp, sp, #0x30

The first instruction is nothing but to grow the call stack. Similar with x64, the call stack address goes downward as the stack grows. In this example, the call stack is grown by 48 bytes. - As we mentioned before,

X29(FP, frame pointer) andX30(LR) are all callee saved, we will have to save the values before moving forward. Instruction 0x100003f80 does exactly this. Later we will see that if we don’t modify any of them in a function, there is no need to store them at the beginning of the function then. - Skipping to instruction 0x100003f98, what it does is to store 0x100003f9c into the

x30(LR) register first and then set thePCto 0x100003f50, the first instruction in the functionInterface.

Before we move forward with this program, let’s quickly take a look inside the function Interface.

10x100003f50 <+0>: sub sp, sp, #0x10

20x100003f54 <+4>: str w0, [sp, #0xc]

30x100003f58 <+8>: ldr w8, [sp, #0xc]

40x100003f5c <+12>: ldr w9, [sp, #0xc]

50x100003f60 <+16>: mul w8, w8, w9

60x100003f64 <+20>: str w8, [sp, #0x8]

70x100003f68 <+24>: ldr w8, [sp, #0x8]

80x100003f6c <+28>: ldr w9, [sp, #0x8]

90x100003f70 <+32>: mul w0, w8, w9

100x100003f74 <+36>: add sp, sp, #0x10

110x100003f78 <+40>: ret- The first instruction (0x100003f50) grows the call stack by 16 bytes.

- The instructions between 0x100003f54 and 0x100003f70 performs the calculation inside the

Interfacefunction. - Instruction 0x100003f74 pops the stack.

- The last ret instruction is simply ask the program to jump to the instruction that

LRregister points to and it is set to 0x100003f9c in the main function by instruction 0x100003f98.

One thing we can notice from this program is that the assembly code in Interface function doesn’t bother to save and restore X29 and X30, this is fine as it never make any changes of these parameters within this function.

After the Interface function is finished, the PC becomes 0x100003f9c, the next instruction after the invoking Interface function.

- Looking at 0x100003fa4, what this program does is to restore the

X29andX30registers. It is important to restore these two registers. Specifically in this program, it is theLRthat is important as once the return instruction is called at 0x100003fac, the main function needs to return to whereLRpoints to. - It is certainly the callee’s responsibilty to make sure the

SPregister is unchanged. Since we grow the stack at instruction 0x100003f7c, we will have to pop the stack so that the SP register is intact.

Similarly, let’s take a look at the asm code produced by the same compiler, but with optimization. Below is the code produced by the compiler with the two functions split into two different compilation units.

Below is the asm code for main.

10x100003fa8 <+0>: b 0x100003fac ; Interface at test.cpp:3:15And here is the asm code for Interface.

10x100003fac <+0>: mul w8, w0, w0

20x100003fb0 <+4>: mul w0, w8, w8

30x100003fb4 <+8>: retThis is very self-exlanatory. I’d like to point out one interesting trick that the compiler did in this case. Please be mindful that the jump instruction is a b rather than a bl instruction like before. This b instruction will not store the return address in the LR register. This is fine as the compiler is being smart by taking advantage of the fact that there is no further instructions after invoking the Interface function. So after the Interface function is done, it directly jumps to the next instruction of whichever code that calls main.

Last, let’s take a look at the asm code produced with link time optimization.

10x100003fac <+0>: mul w8, w0, w0

20x100003fb0 <+4>: mul w0, w8, w8

30x100003fb4 <+8>: retVery simple code and that does exactly what we need.

Quick Summary Before Moving Forward

In this section, we briefly mentioned some of the basics of how CPU handles call stack on both x64 and Arm64 architecture. We are also clear by now which registers are callee saved and which are caller saved.

Even though what we touched is simply a tip of the iceburg, this should serve as a good foundation for us to keep learning what a fiber is and how it can yield when needed.

Existing Fiber Interface on Windows

Next, before we finally dive into the implementation detail of fiber, let’s take a quick look at what kind of interface the Windows operating system offers for fiber. It is actually really easy to use.

ConvertThreadToFiber: This is a function helps to convert the current thread to a fiber. It is mandatory to convert a thread to a fiber before yielding the control to another fiber.ConvertFiberToThread: This function is the reversed version of the previous function. It converts the current fiber to the original thread that was converted to it in the first place.CreateFiber: This is the interface for creating a fiber. Programmers can specify the size of the stack and the entry function pointer of the fiber so that when it first gains control, it would run from there.DeleteFiber: As its name implies, this is to ask the OS to delete the fiber. Of course, it is programmer’s responsibility to make sure a running fiber is not deleted, which will quite possbily cause crash.SwitchToFiber: This is the juicy part. This is the interface that allows fiber to yield to another fiber. And this function implementation is quite cheap, the performance cost is no where near a thread switch scheduled by the OS.

That is it. This is the essential part of fiber interfaces that is required to implement a job system that allows yielding in the middle of a task. As we can see, it is really not complicated at all.

For readers who still have confusion how to use these, here is a short example that demonstrates how to use the interfaces.

1#include <iostream>

2#include <Windows.h>

3

4#define FiberHandle LPVOID

5

6void RegularFunction(FiberHandle* fiber)

7{

8 // We are done executing this fiber, yield control back

9 SwitchToFiber(fiber);

10

11 std::cout << "Hello Fiber Again" << std::endl;

12}

13

14void WINAPI FiberEntry(PVOID arg)

15{

16 // this is the fiber that yields control to the current fiber

17 FiberHandle* fiber = reinterpret_cast<FiberHandle*>(arg);

18

19 // do whatever you would like to do here.

20 std::cout << "Hello Fiber" << std::endl;

21

22 RegularFunction(fiber);

23

24 // We are done executing this fiber, yield control back

25 SwitchToFiber(fiber);

26}

27

28int main(int argc, char** argv) {

29 // convert the current thread to a fiber

30 FiberHandle fiber = ConvertThreadToFiber(nullptr);

31

32 // create a new fiber

33 FiberHandle new_fiber = CreateFiber(1024, FiberEntry, fiber);

34

35 // yield control to the new fiber

36 SwitchToFiber(new_fiber);

37 SwitchToFiber(new_fiber);

38

39 // convert the fiber back to thread

40 ConvertFiberToThread();

41

42 // delete the fibers

43 DeleteFiber(new_fiber);

44

45 return 0;

46}In case there is confusion, here is a quick explaination. The execution order is that the main gets executed until line 36, where it gives the control to the new fiber created on line 33.

After the yielding, the function main will no longer be in control anymore, CPU will start execute from line 14 then. Please be mindful that on line 9, the program jump directly from within RegularFunction, which as its name implies is just a regular c++ function, to the main function so that it keeps execution on line 37. There is no need to go through FiberEntry for such a jump. It is also possible to jump anywhere deep in the callstack of a fiber. Since line 37 immediately yields control back to the fiber, the new_fiber gains the control the second time except that this time, it resumes executing from where it was suspended before (line 9), rather than starting from scratch again. Last, but not least, it is programmers responsibility to make sure fiber always yields to the correct fiber for execution. In this case, line 25 makes sure that the control is back to main so that the rest of the main function gets execution. Do not expect compiler to help in this case, it doesn’t have enough information to make such a decision.

Hopefully, through this simple example, readers can understand the power and flexibility of fiber. It offers greater power that is badly needed in a job system with tons of dependencies.

Implementing Fiber on x64

This blog post wouldn’t exsit if it isn’t this fun part. The real fun begins in this section when we start to mess around with the registers to fool the CPU so that we can switch fiber like the OS provided interface does. In order to make this blog post more educational, I made a tiny library that does just this. Here is the link to the Github gist repo I created. Readers are recommended to read this blog post along with the source code to gain a deeper understanding of the tech.

As a matter of fact, such an implementation is needed on MacOS since the OS doesn’t offer interfaces for fiber control by the time this post was written. There was indeed an ucontext interface exists on MacOS. However, it was deprecated. Using such an interface would be risky in the future. On linux, we can indeed using this for achieving the same thing.

The process of implemeting the fiber interface should be pretty rewarding. And the x64 fiber implementation that we will mention in this section will work on all platforms that supports System V ABI.

To implement fiber on x64 by ourselves, all we need to do is to implement the 5 interfaces we mentioned above. As a matter of fact,

a good news here is that there is very little needs to be done in ConvertThreadToFiber and ConvertFiberToThread. Later we will explain why this is the case. This leaves us only three functions to implement, CreateFiber, DeleteFiber and SwitchToFiber.

Fiber Structure Definition

To get started, we need to define the fiber structure first. Below is the definition of fiber in my implementation. Let’s take a quick look at it first.

1//! Abstruction for fiber struct.

2struct Fiber {

3 /**< Pointer to stack. */

4 void* stack_ptr = nullptr;

5 /**< fiber context, this is platform dependent. */

6 FiberContexInternal context;

7};As we can see from this data structure, there is only two members in it. stack_ptr, as its name implies, is simply the pointer to the address of the stack, which will be used by the fiber. Different from regular subroutine or language supported coroutine, fiber requires programmers to allocate its own stack memory by themselves. With Windows fiber interface, it is done under the hood of CreateFiber. However, with a low level asm implementation like this, we need to carry over the responsibility of creating the stack memory. In reality, this explicit control of memory allocation is commonly quite welcome by game developers since they are in charge of the memory allocating rather than handling it over to a third party library. Be mindful that there is no real requirement where the memory this pointer has to point to, it is commonly on heap, but it is totally fine if this fiber stack memory is allocated on another stack of either a fiber or a thread as long as the synchronization is done properly that the fiber stack memory won’t get destroyed before it is done being used. The only reason we are keeping track of this is because we would like to properly deallocate this memory properly when the fiber gets destroyed. Assembly code will not use this member to track the stack at all. Instead, it will use a stack pointer, which is stored in FiberContextInternal, to keep track of the stack.

context is the data structure that keeps track of the registers. The mystery fiber context structure merely keeps track a few registers, specifically defined as below.

1struct FiberContexInternal {

2 // callee-saved registers

3 Register rbx;

4 Register rbp;

5 Register r12;

6 Register r13;

7 Register r14;

8 Register r15;

9

10 // stack and instruction register

11 Register rsp;

12 Register rip;

13};Some readers may have a question by now. What is the rationale behind the choices of the registers that need to be stored? This is a very important question for us to understand how it works. To answer the question, let’s take a look at the registers in the data structure.

- Why do we need to store

RIP?

This is a truly simple question. As mentioned previously, theRIPis the instruction pointer, which points to the next instruction to be executed by the CPU.FiberContextInternalis the data placeholder between a fiber suspension and fiber resume. Upon suspension, the fiber needs to know where it is suspended on so that when it gets resumed, it knows what is the next instruction for the CPU to execute so that it resumes from exactly where it was suspended. - Why do we need to store

RSP?

This is an easy question to answer as well. Since we allocate our own fiber memory, theRSPhas to point to its own stack. Since the compiler doesn’t know where the stack top is, we need to make sure we know where it is. And thisRSPdoes exactly that. - Why do we need to store the callee saved registers?

Imagine we have a function A made a fiber switch from fiber 0 to fiber 1. Assuming that theR12register written right before the switch. After the swicth, the function A will be suspended and the fiber 1 will be either resumed or launched. If the fiber 1 was suspended before and gets resumed, the following instructions of fiber 1 may read the registerR12as well. However, it is by no means interested in reading the value ofR12written by function A, all it needs to know is what theR12register’s value was before it was suspended. On the other hand, the value written to theR12register by function A may very likely to be read at a later point inside it as well. To prevent this value from getting lost after it is resumed in the future, it needs to be cached somewhere. The same goes true for not onlyR12, but also all callee saved registers. And this is why we need to keep all the callee saved registers. - Why don’t we care about caller saved registers?

If we take a look at the same example as above, we should be mindful that the fiber switch is a function itself. Even if the fiber switch is just a regular subroutine, as long as it is not inlined, the compiler needs to make sure it restores the values of caller saved registers after it is called. In the above example, imagine after the fiber switch if some other fiber overwrites the value of the caller saved registers and switch the control back to fiber 0, it is still the compiler’s responsibility to make sure the caller saved registers are properly restored before reusing them in the caller code. Such a restoring process is commonly performed through caching the value on stack. To some degree, we can regard the call stack itself as the partial cache of our fiber context so that it frees us from the need of doing so.

To emphasize it, it is quite important for us to make sure compiler won’t optimize our fiber switch function into an inline version. As otherwise, we would need to be responsible for storing the caller saved registers in the fiber context as well. Depending on how aggressive compiler optimization is, it may not be good enough to simply put this function definition into another compilation unit, especially when link time optimization is enabled. The most secured way to make sure is to take a look at the assembly code produced by the compiler to be sure it does what we expect.

At this point, I believe it should be clear why we are defining the fiber context structure the way it is. Thanks to the fact that all of the SIMD registers are caller saved, we only need to store a few registers in our fiber context.

Switch Between Fibers

Rather than starting from the CreateFiber, I choose to start with the SwitchFiber interface as the former requires knowledge about how the latter works. We already learned that CPU will only use its registers to talk to the rest of the system unless something could be compile time resolved, for example function addresses. Since static information is the same for all executing threads/fibers, we just care about registers for a fiber switch then. Because we are working with registers, we will have to touch assembly languages in order to achieve it. Below is the switch fiber implementation I’ve done on x64 architecture.

1.text

2.align 4

3_switch_fiber_internal:

4 // Store callee-preserved registers

5 movq %rbx, 0x00(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RBX */

6 movq %rbp, 0x08(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RBP */

7 movq %r12, 0x10(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R12 */

8 movq %r13, 0x18(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R13 */

9 movq %r14, 0x20(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R14 */

10 movq %r15, 0x28(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R15 */

11

12 /* call stores the return address on the stack before jumping */

13 movq (%rsp), %rcx

14 movq %rcx, 0x40(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RIP */

15

16 /* skip the pushed return address */

17 leaq 8(%rsp), %rcx

18 movq %rcx, 0x38(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RSP */

19

20 // Load context 'to'

21 movq %rsi, %r8

22

23 // Load callee-preserved registers

24 movq 0x00(%r8), %rbx /* FIBER_REG_RBX */

25 movq 0x08(%r8), %rbp /* FIBER_REG_RBP */

26 movq 0x10(%r8), %r12 /* FIBER_REG_R12 */

27 movq 0x18(%r8), %r13 /* FIBER_REG_R13 */

28 movq 0x20(%r8), %r14 /* FIBER_REG_R14 */

29 movq 0x28(%r8), %r15 /* FIBER_REG_R15 */

30

31 // Load stack pointer

32 movq 0x38(%r8), %rsp /* FIBER_REG_RSP */

33

34 // Load instruction pointer, and jump

35 movq 0x40(%r8), %rcx /* FIBER_REG_RIP */

36 jmp *%rcxBelow is the declaration of the fucntion interface

1void _switch_fiber_internal(FiberContexInternal* src_fiber, const FiberContexInternal* dst_fiber);There are two parameters in this funciton, src_fiber and dst_fiber. In the above assembly code, RDI is the first parameter (src_fiber) and RSI is the second parameter (dst_fiber). The assembly code is so simple that it doesn’t need detailed explanation. In a nutshell, it takes the contents of the relevant registers (RBX, RBP, R12 to R15, RIP, RSP) and store them in the fiber context that src_fiber points to, after which it also loads the content in the fiber context pointed by dst_fiber into the registers. After swapping the values in the registers, the CPU is then fooled about its execution sequence. It will forget all the previuos instruction context and pretend that this funciton is called from where dst_fiber is left of last time, which also includes the initial state of the dst_fiber.

Next obvious question is that where does the value of the fiber context pointed by the dst_fiber come from. There are two cases then. If the fiber was suspended before, it must have went through the same interface, which must have populated the fiber context with the correct value through the first half of the _switch_fiber_internal function. Of course, it is programmers responsibility to make sure the fiber switch is legit. Incorrect fiber switch will easily crash the program.

However, if the fiber is newly created and never gets executed before, we also need to make sure it works as expected.

Creating a new Fiber

Now that we know how to switch between fibers, a question remained to be answered is how can we create a fiber from scratch so that it can be used as a destination fiber in the above switchfiber call.

Let’s first of all define a fiber main function, which serves as the beginning of a fiber’s execution

1void FiberMain(){

2 // do whatever you want to do in this fiber

3}

My fiber entry is defined as above. Though, it is totally possible to define it other ways. This is just one possibility. The next step is to hook this function with a fiber so that when it first gains control, it will start from this function.

1bool _create_fiber_internal(void* stack, uint32_t stack_size, FiberContexInternal* context) {

2 // it is the users responsibility to make sure the stack is 16 bytes aligned, which is required by the Arm64 architecture

3 if((((uintptr_t)stack) & (FIBER_STACK_ALIGNMENT - 1)) != 0)

4 return false;

5

6 uintptr_t* stack_top = (uintptr_t*)((uint8_t*)(stack) + stack_size);

7 context->rip = (uintptr_t)FiberMain;

8 context->rsp = (uintptr_t)&stack_top[-3];

9 stack_top[-2] = 0;

10

11 return true;

12}Above is an implementation for on x64 architecture. It is actually quite simple, all we need to do is to setup the stack pointer and instruction pointer. Since the instruction pointer points to the FiberMain, the fiber will be launching from this function entry point first, exactly meeting our expectation. For the stack, we can pass in any memory as long as we can be sure during the execution of the fiber, this memory won’t get destroyed. The stack memory has to be 16 bytes aligned, which is required by the ABI. As mentioned before, the stack’s address grows downward, meaning that every time we push something in the stack, the stack top address decreases. And because of this, we have to set the stack pointer to the end of the memory, rather than the beginning of the memory.

If we think about the first time such a fiber gets executed, the second half of the _switch_fiber_internal function will simply load garbage values in the callee saved registers except rsp and rip, but this is fine as the compiler will make sure that the callee saved registers will not be read before they are written to.

There is one annoying thing in the above design. The FiberMain function doesn’t have any connection with the creation code. Of course, it is possible to pass the information through global data with careful synchronization. A better alternative is to allow programmers to pass in one pointer to the FiberMain so that it can access to basic information from the FiberMain about its creation code. If you can pass in a pointer, you can pass in anything then.

To make it happen, we need to add one more register in our fiber context. And this register is RDI, which is used to represent the first argument passed in a function.

1struct FiberContexInternal {

2 // callee-saved registers

3 Register rbx;

4 Register rbp;

5 Register r12;

6 Register r13;

7 Register r14;

8 Register r15;

9 // stack and instruction register

10 Register rsp;

11 Register rip;

12 // the first parameter

13 Register rdi;

14};With this one extra register, we can simply pass a pointer from our redefined interface this way

1bool _create_fiber_internal(void* stack, uint32_t stack_size, void* arg, FiberContexInternal* context) {

2 // it is the users responsibility to make sure the stack is 16 bytes aligned, which is required by the Arm64 architecture

3 if((((uintptr_t)stack) & (FIBER_STACK_ALIGNMENT - 1)) != 0)

4 return false;

5

6 uintptr_t* stack_top = (uintptr_t*)((uint8_t*)(stack) + stack_size);

7 context->rip = (uintptr_t)FiberMain;

8 context->rdi = (uintptr_t)arg;

9 context->rsp = (uintptr_t)&stack_top[-3];

10 stack_top[-2] = 0;

11

12 return true;

13}And of course, we need to make some adjustment in our assembly code as well.

1.text

2.align 4

3_switch_fiber_internal:

4 // Store callee-preserved registers

5 movq %rbx, 0x00(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RBX */

6 movq %rbp, 0x08(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RBP */

7 movq %r12, 0x10(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R12 */

8 movq %r13, 0x18(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R13 */

9 movq %r14, 0x20(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R14 */

10 movq %r15, 0x28(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_R15 */

11

12 /* call stores the return address on the stack before jumping */

13 movq (%rsp), %rcx

14 movq %rcx, 0x40(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RIP */

15

16 /* skip the pushed return address */

17 leaq 8(%rsp), %rcx

18 movq %rcx, 0x38(%rdi) /* FIBER_REG_RSP */

19

20 // Load context 'to'

21 movq %rsi, %r8

22

23 // Load callee-preserved registers

24 movq 0x00(%r8), %rbx /* FIBER_REG_RBX */

25 movq 0x08(%r8), %rbp /* FIBER_REG_RBP */

26 movq 0x10(%r8), %r12 /* FIBER_REG_R12 */

27 movq 0x18(%r8), %r13 /* FIBER_REG_R13 */

28 movq 0x20(%r8), %r14 /* FIBER_REG_R14 */

29 movq 0x28(%r8), %r15 /* FIBER_REG_R15 */

30

31 // Load first parameter

32 movq 0x30(%r8), %rdi /* FIBER_REG_RDI */

33

34 // Load stack pointer

35 movq 0x38(%r8), %rsp /* FIBER_REG_RSP */

36

37 // Load instruction pointer, and jump

38 movq 0x40(%r8), %rcx /* FIBER_REG_RIP */

39 jmp *%rcxWith all the above change, we introduce an argument in the FiberMain. And that single argument allows us to access anything we want within the FiberMain.

1void FiberMain(void* arg){

2 // do whatever you want to do in a this fiber

3}

Careful readers may already notice a performance inefficiency here. As long as a fiber has been executed, line 32 is useless. In pratice, I doubt this one single cycle of instruction may have any performance impact at all. Similar to this inefficiency, if we have a new fiber gaining control through the fiber switch call, the instructions between 24 and 30 are all useless as well. A solution to this problem is to warm up the fiber upon its creation through a simplified assembly function that doesn’t have line 24 and 30 by switching to the newly created fiber right after creation. And the fiber can switch back at the beginning of its FiberMain to the creation fiber immediately to give its control back. The caller code won’t even notice a thing about such a round trip. And then we can remove the instruction loading the first paremter through a separate assembly function that is only used for future fiber switch. For simplicity, my implementation doesn’t implement this optimization.

Converting between a Thread and a Fiber

Now we are able to create a fiber and switch to the fiber from a different fiber. There is one question left. Our program starts from a thread, not a fiber. We need to be able to convert the thread to a fiber so that it allows us to make the switch happens because we can’t switch from a thread to a fiber.

In order to do so, we need to implement two different functions, ConvertToFiberFromThread and ConvertToThreadFromFiber. Let’s start with the first one.

Different from newly created fibers by the function CreateFiber, which are by default in its suspended mode, fibers created through ConvertToFiberFromThread are already running when they are ‘created’, or specifically, converted. This newly converted fiber should be used as source fiber so that it switches to some other fiber. Under no circumstances that we should switch from a fiber to a newly converted fiber produced by ConvertToFiberFromThread, which makes no sense.

Taking advantages of this fact, we can imagine that the default stack pointer or instruction serves no purpose in such a converted pointer anywhere. No code will ever read those two members (RIP, RSP) in the fiber context before it is first written by a fiber switch. The same goes true for all registers in FiberContexInternal. This gives us the freedom to ignore such fields during a thread to fiber conversion.

1inline FiberHandle CreateFiberFromThread() {

2 Fiber* ptr = (Fiber*)TINY_FIBER_MALLOC(sizeof(Fiber));

3 ptr->context = {};

4 return ptr;

5}Above is the function to convert from a thread to a fiber. Apart from allocating the fiber structure memory, not even the fiber stack, nothing else is done. Again, this is totally fine as this fiber context will not be read first.

It is pretty straightforward to figure out that ConvertToThreadFromFiber is simply an empty implementation. An alternative solution is to choose deleting the fiber in such a function to be more consistent with the Windows interface. However, in my own implementation, I hided the interface from the library. It is automatically done once the fiber’s lifetime ends.

Deleting a Fiber

Deleting a fiber is the simplest method compared with all the above methods. All we need to do at this point is to free the stack memory and the memory for the fiber structure itself.

To point it out again, deleting a running fiber can result in crash if it is being ran or will be ran in the future. It is programmers’ responsibility to make sure when a fiber is deleted, nothing is using it.

Troubles Introduced by Fibers

At this point, I believe we have figured out how fiber works under the hood. As we can see from the implementation, fiber works by hacking the registers to fool CPU so that it swaps the call stacks and other relevant information for the CPU to make a switch. It is extremely cheap to make such a switch. There is great flexibility introduced with the tech. And it can be quite useful for game engine’s job system design.

However, while embracing the benefits of fibers, we have to be aware of the risks and responsibilities we are taking in the mean time to avoid problems.

Do not Exit the FiberMain

As we learned before, there is ways for comiplers to make sure the returned address is properly setup when a function is called. However, we have to be mindful that a fiber entry function has no return address. It is not called in a conventional way. Do not expect the fiber returns its control back to whoever gave its control in the first place, it won’t happen automatically.

So we have to make sure that the fiber entry function will never exit regularly like other regular functions. What we should do is to make a switch to some other fiber once it is not expected to be executed anymore. It is fine to terminate the fiber even if the fiber entry function is not fully finished. It is actually mandatory to avoid unexpected behavior. An alternative is to setup the return address properly. Though, this will make the fiber implementation a bit more complicated and there is little that we will gain in doing so.

Smart Memory Pointers

Smart pointers is a mechanism to prevent memory leak. For every piece of heap memory allocation, it will couple this allocation with a smart pointer allocation, which is a small object that controls the life time of the heap memory. As long as the smart pointer itself gets destroyed, the heap allocation coupled with it is gurranteed to be freed as well. If all the smart pointers are allocated on stack, as we know by the end of a program all stack memory gets properly popped, we can easily deduce that all the heap allocation is freed as well. The mechanism also extends to smart pointer themselves allocated on a heap, which itself is controled by another smart pointer on a stack. The memory dellocation will happen recursively to any depth level when the top level smart pointer dies.

One of the corner cases that makes this mechanism invalid is fiber. Imagine you have a fiber with its fiber stack on a heap. Inside this fiber, we use a smart pointer allocating some memory on a heap. However, the fiber then gets suspended and never gets resumed before the fiber gets destroyed. What will happen here is that the smart pointer sitting on the fiber stack, which is essentialy on a heap, will be leaked. This is different from allocating a object with a smart pointer as its member variable on a heap, when this object goes out of scope, it will destroy the heap allocation bundled with the smart pointer member. This can be done as the compiler is in a good position to make sure it happens. However, similar case mentioned won’t work for fibers as the compiler knows nothing about how we use our fiber stack.

So with fibers, it is techinically possible to introduce memory leak even if your whole program’s memory allocation is guarded with smart pointers. We certainly need to pay attention to avoid it. One way to make sure it won’t happen is to leave a fiber switch right before the end of a FiberMain function and always execute to make the last fiber switch. And even with this, one needs to make sure there is no smart pointer whose life time still exists after the last fiber switch.

Object Destruction

We mentioned that we can’t allow fiber entry function to exit normally. This means that we have to yield control to other fibers before it ends. This could mean we may still have active objects living on that stack, like the smart pointers we talked about. In more generalized sense, any objects, besides smart pointers, may need to destruct properly. Same as smart pointers lose its control over memory management, if we have an object taking advantage of its destructor to do something important, it may get skipped as well.

It is programmers’ responsibility to make sure when a fiber gets destroyed, nothing left in the fiber needs to be executed. Commonly compilers can safe guard it for us, but not in a fiber environment.

To be clear, compiler behavior is totally normal within a fiber stack. This means that if you have an object that lives on a call stack, which gets popped, the compiler will make sure the destroctor gets called properly. What we need to be careful about is to make sure no pending destructor needs to be executed when fiber gets destroyed.

No Fiber Reset in Windows’ Fiber Interface

This is more of an inconvenience than a problem. Fiber is commonly seen in a job system in game engines. Such job systems commonly fixes thread on physical CPU cores through thread affinity. Fiber is like a job container, a job can only be executed when it finds an available idle fiber and a thread. Once it is done executing, the fiber will be put back to a pool of idle fibers. When we put a used fiber back to the idle fiber pool, we don’t really care about its previous execution state anymore. A nice thing that can be done is to reset the fiber to its initial state before putting it in the idle fiber pool. This can be easily achieved through assembly implementation as we can simply reset the fiber context like we did when we created the fiber. Of course, we should not reset a fiber converted from a thread as it makes little sense anyway.

That simple solution has a problem as Windows doesn’t provide an interface to reset a fiber. An unrealistic solution is to delete the fiber and recreate one every time we need to put it back in the idle pool, which pretty much works the same as no idle fiber pool, unfortunately. Since Windows create fiber interface doesn’t allow us to allocate our own stack. Fiber allocation on Windows is couple with a memory allocation under the hood, making it a bit expensive. Given the high frequency of job execution during a frame in a game engine, this is by no means a good solution.

There are at least two solutions to this problem. One of the solutions is simply to implement an assebmly based fiber interface on Windows. This shouldn’t be too hard at all since we have already implemented on both of x64 and Arm64 architecture. It is most likely just a matter of toggling a few macros.

The other solution is to put an inifinite loop inside a FiberMain function, like this.

1void FiberMain(void* arg){

2 while(true){

3 // execute the task here

4 DoTask();

5

6 // yield the control back to another fiber

7 SwitchFiber(current_fiber, other_fiber);

8 }

9}This goes beyond the topic of a fiber library itself. It is more about a job system. I’ll briefly mention a few details here

- An idle fiber should either start from the first line or line 8, which is the end of the last loop iteration.

- Be mindful that it is totally legit for us to yield the control to any other fiber within the

DoTaskfunction. We can yield anywhere deep inside the fiber call stack. - The

other_fibercan be either a waiting-for-task fiber or a previously suspended fiber. Which fiber to pick is topic of job system scheduling problem.

Cross Thread Fiber Execution

Different job systems have different policies. There is one important decision to make in every fiber based job system. That is about whether to allow a suspended fiber to resume on another thread. There is clearly some trade off here to consider.

- If we do allow doing so, we will have to implement all the system provided sychronization primitives like mutex, conditional variable. And we can’t use thread local storage as freely as before. This is not to say we can use TLS at all, we just need to be careful that our TLS access pattern should not cross a fiber switch as before the switch, TLS could be from thread A and after the thread it could be from thread B, this will easily crash the problem.

- If we do not allow it. We can use all the above mentioned forbidden things. However, the load balancing may not be as good as the other way around. Think about there 4 threads ( 4 physical cores ), all of which are pulling for tasks. While the first thread somehow pulls 100 tasks, which all gets suspended soon after execution, while other three threads are just pulling tasks that never gets suspended. After the task pool is exhausted, the other three threads may be done executing at a later point. However, since the 100 tasks are already scheduled to thread 1 and if the system doesn’t allow cross thread fiber execution, we will have to wait for thread 1 to finish executing all the 100 tasks to be done, when the other threads are waiting idling.

In an ideal world, for performance consideration, we should consider allowing cross thread fiber execution. This would certainly mean that we are taking a lot more responsibility than the other way around.

Stay Vigelent Against Compiler Optimization

Compiler optimization has always been our best friend. It optimizes code for us without us doing anything low level. However, in such a fiber environment, where we hack low level registers, things can go very wrong if we are not careful enough.

To name a concrete example, just now we briefly mentioned that as long as the TLS memory access pattern is not crossing fiber switch, it should be fine. In reality, this turns out to be problematic due to a low level compiler optimization that the compiler is allowed to optimize TLS memory access with cache for better performance. To make it clear, let’s take a look at the following code snippet.

1thread_local int tls_data = 0;

2void WINAPI FiberEntry(PVOID arg)

3{

40x00B21010 push ebp

50x00B21011 mov ebp,esp

60x00B21013 push ecx

70x00B21014 push esi

80x00B21015 mov esi,dword ptr fs:[2Ch]

90x00B2101C push edi

100x00B2101D mov edi,dword ptr [__imp__SwitchToFiber@4 (0B23004h)]

110x00B21023 nop dword ptr [eax]

120x00B21027 nop word ptr [eax+eax]

13 while (true)

14 {

15 volatile int k = tls_data;

160x00B21030 mov eax,dword ptr [esi]

17 SwitchToFiber(thread_fiber);

180x00B21032 push dword ptr [thread_fiber (0x0B253F4h)]

190x00B21038 mov eax,dword ptr [eax+4]

200x00B2103E mov dword ptr [k],eax

210x00B21041 call edi

22 }

230x00B21043 jmp FiberEntry+20h (0x0B21030h)

24}Above is a mixed view between c++ and assembly code for better visibility. I purposely mark the temporay variable k with volatile to avoid compiler optimizing it out since it is not read anywhere.

A very subtle bug is hidden in this code. We can notice that the value of the volatile variable k is set from the register eax through line 20. And the eax comes from the esi through instruction at line 16. However, the esi value is loaded before the program enters the loop. So that said the compiler is trying to be smart by assuming that the code loop will always run on the same thread so that it can cache the memory fetch through line 8. This is not a bad assumption most of the time. However, we know that there is a legit risk that loop iterations could been executed on different threads. And this optimization will lead the program to read the TLS of incorrect thread, easily causing crash.

On Windows, there is a dedicated flag /GT for avoiding such fiber unfriendly optimization. However, such a flag doesn’t exist on some other platforms. In that case, what we can do is to prevent the compiler from being smart by isolating the access to TLS inside a non-inlined function. A common approach is to define the access method in a different compilation unit. As mentioned before, we still need to be careful about compilers’ link time optimization to inline it again.

Stepping into a FiberSwitch

Besides functionality, debugability is almost equally important.

Different from threads, suspended fibers are pretty much invisible to debuggers. For example, if we pause a function in a fiber, even if we have other suspended fibers in the air, Visual Studio’s parallel call stack will not have visibility of the suspended fibers. This certainly makes debugging a bit tricky in some cases, especially when it involves sychronization issues. I personally found out that printing log is a viable option to gain more information about suspended fibers.

Another detail that we need to pay attention is the ability to step into a fiber switch call. Most of the time, we don’t care about the detailed implementation in it, but our bottom line is that we should be able to step through this call to get over to the other side of the fiber switch, the target fiber code. GDB and LLDB work pretty well for this as fiber implementation is done through assembly code. However, Visual Studio has a flag that has big impact on the behavior whenever it comes to steping into a fiber switch. One can locate this flag with the following setup, Project Property Page -> Configuration Properties -> Advanced -> Advanced Properties -> Use Debug Library. If we want to step into the fiber switch function like we do with other regular functions, this needs to be set to true. Otherwise, the debugger will simply step over it without going to the other side of the fiber switch.

Avoid Making Any Blocking Calls

Certain opertions, like IO read, will block the thread execution for a while because of the wait. When such a block happens, the OS commonly put this thread on hold and assign some other thread to the physical core for further execution to utilize the available hardware cores.

However, fiber based job system commonly use thread affinity to fix threads on physical cores. The number of threads should be the same with the number of physically available cores. Fiber is our new user mode thread concept that allows task switching a lot faster. We should be extremely careful to avoid making blocking calls in a fiber, there will be no other thread in the same application for the OS to schedule anymore to fill in the gap while waiting for IO.

However, we can’t avoid IO calls in a game. A solution in game engine is to allocate background threads that is dedicated for such calls. And only execute blocking calls on those threads rather than any fibers to avoid it.

Summary

In summary, we mentioned a lot about fibers in this post. Starting from the very basics about CPU architecture, and then a detailed fiber implementation, all the way to the problems with fibers.

As we can see, fiber offer great flexibility that is commonly not available through other methods, which is why it is favored by game studios seeking for better performance. Of course, the power of fiber is clearly not limited to game development alone. It can be used in mostly all CPU computational intensive software that cares about performance.

Reference

[1] Preemption (computing)

[2] Here’s how Intel® Hyper-Threading Technology (Intel® HT Technology) helps processors do more work at the same time

[3] C++ Coroutines: Under the covers

[4] Building a Coroutine based Job System without Standard Library

[5] Combining Co-Routines and Functions into a Job System

[6] Parallelizing the Naughty Dog Engine Using Fibers

[7] Computer multitasking

[8] Cooperative multitasking

[9] Introduction to C++ Coroutines

[10] Fibers, Oh My!

[11] Modern x86 Assembly Language Programming

[12] AVX-512

[13] x86 Assembly Guide

[14] System V Application Binary Interface AMD64 Architecture Processor Supplement

[15] Programming with 64-Bit Arm Assembly Language

[16] Parameters in NEON and floating-point registers

[17] Procedure Call Standard

[18] Fiber (computer science)

[19] Back to Basics: C++ Smart Pointers

[20] System V ABI